La Monnaie, Brussels, Sunday February 2 2014

Conductor: Ludovic Morlot. Production and sets: Alvis Hermanis. Costumes: Anna Watkins. Lighting: Gleb Filshtinsky. Video: Ineta Sipunova. Jenůfa: Andrea Danková. Laca Klemeň: Charles Workman. Števa Buryja: Nicky Spence. Kostelnička Buryjovka: Jeanne-Michèle Charbonnet. Stařenka Buryjovka: Carole Wilson. Stárek: Ivan Ludlow. Rychtář: Alexander Vassiliev. Rychtářka: Mireille Capelle. Karolka: Hendrickje Van Kerckhove. Pastuchnyňa: Beata Morawska. Jano: Chloé Briot. Barena: Nathalie Van de Voorde. Tetka: Marta Beretta. Orchestra and Chorus of La Monnaie.

Let me see...

Behind a Mucha-style curtain, the stage was strictly partitioned, with a strip of apron in front of a second proscenium divided into four main spaces: tall vertical panels to either side and, in the middle space, a large screen above a lower "letter-box" opening. The screens were used for projections and the large upper one could rise to reveal a bright, stepped space for the chorus.

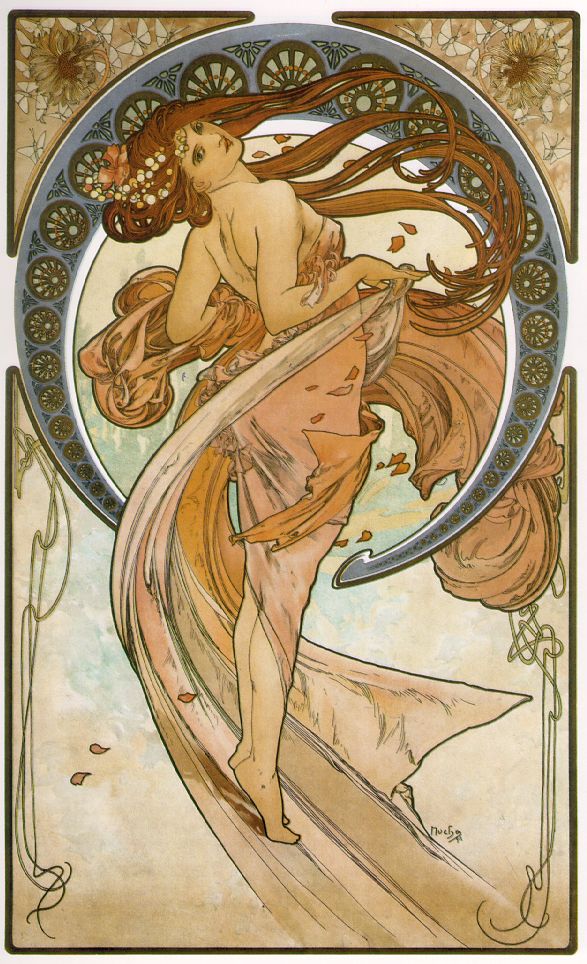

The parti pris was to stage the outer acts as a "poetic" (so the programme notes had it; "scrapbook", I might have said) encounter between Moravian folk art and the more sophisticated aesthetic currents prevailing in Prague at the time of the opera. The action was played out puppet-style, with stylized, Kabuki-inspired gestures, in sumptuously embroidered traditional costumes: the women with lampshade skirts and puffed sleeves the size of footballs; the men with elaborately flowered and feathered headgear. La Monnaie's workshops are said to have worked on these clothes for a year. Art nouveau motifs and images, some rotating, were projected, biscuit-tin style, on the screens, while a fascinating, Rite-of-Spring ballet was danced in the letter-box space by girls in plain cream.

In absolute contrast, the middle act was set, in the letter-box, in a grimy, contemporary kitchen, with a gas stove and fridge-freezer to the right, a rusty iron bedstead to the left, snow falling heavily behind icy windows, bare bulbs, pious images, and everyday modern clothes.

The trouble with this approach, apart from the fact that the "hieratic" acting was only half-heartedly done - as is often the case when a director decides to do it - was that the outer acts were stripped of any dramatic impact and reduced to a mere visual feast. The crux of the drama - deep-freezing the baby - may be in act two, but Jenufa is disfigured for life in act one and the baby does, after all, thaw out in the middle of her wedding in act three...

And though Jeanne-Michèle Charbonnet is a great actress, the grim and grimy reality of act two was not especially convincingly directed, and stuffing the baby's clothes into the freezing compartment in an act of madness before collapsing at the end was simply odd.

Vocally, Andrea Danková was an excellent Jenufa. Jeanne-Michèle Charbonnet has no top left and has to resort to screams instead of singing, but as I just said she's still a great actress with striking presence and this "cheating" is therefore done to great effect. They made a very fine pair. Nicky Spence has, I was told, a "big sound" but it didn't make it too well up to where I was sitting. Many people were impressed by Charles Workman's Steva; I bow to them. I'm not keen, as I've often remarked, on his "stiff" sound that, to me, never seems to open up. He's a good actor, but in this production had little chance to show it, being bound up in the stylization.

I read in the press that Ludovic Morlot was at least better in Janacek than in Mozart. To me, this Jenufa sounded more like a reading than a performance, lacking in variety and subtlety.

Jenufa should be electrifying. This lavish but conspicuously self-conscious production has been described as "magical". To me it was just a disappointment.

Conductor: Ludovic Morlot. Production and sets: Alvis Hermanis. Costumes: Anna Watkins. Lighting: Gleb Filshtinsky. Video: Ineta Sipunova. Jenůfa: Andrea Danková. Laca Klemeň: Charles Workman. Števa Buryja: Nicky Spence. Kostelnička Buryjovka: Jeanne-Michèle Charbonnet. Stařenka Buryjovka: Carole Wilson. Stárek: Ivan Ludlow. Rychtář: Alexander Vassiliev. Rychtářka: Mireille Capelle. Karolka: Hendrickje Van Kerckhove. Pastuchnyňa: Beata Morawska. Jano: Chloé Briot. Barena: Nathalie Van de Voorde. Tetka: Marta Beretta. Orchestra and Chorus of La Monnaie.

Let me see...

- Janacek was Moravian. So was Mucha.

- Jenufa is set in a Moravian village.

- Moravian folk costume is unexpectedly lavish.

- Kabuki uses lavish costumes and is highly stylised.

- Mucha and art nouveau were all the rage in Prague at the time.

- The ballets russes were all the rage elsewhere. Shame they didn't tour to Prague.

- In Jenufa, the crux of the drama - deep-freezing the baby - is in act two. That takes place à huis clos; acts one and three are more public, less intense.

|

| Janacek |

The parti pris was to stage the outer acts as a "poetic" (so the programme notes had it; "scrapbook", I might have said) encounter between Moravian folk art and the more sophisticated aesthetic currents prevailing in Prague at the time of the opera. The action was played out puppet-style, with stylized, Kabuki-inspired gestures, in sumptuously embroidered traditional costumes: the women with lampshade skirts and puffed sleeves the size of footballs; the men with elaborately flowered and feathered headgear. La Monnaie's workshops are said to have worked on these clothes for a year. Art nouveau motifs and images, some rotating, were projected, biscuit-tin style, on the screens, while a fascinating, Rite-of-Spring ballet was danced in the letter-box space by girls in plain cream.

In absolute contrast, the middle act was set, in the letter-box, in a grimy, contemporary kitchen, with a gas stove and fridge-freezer to the right, a rusty iron bedstead to the left, snow falling heavily behind icy windows, bare bulbs, pious images, and everyday modern clothes.

The trouble with this approach, apart from the fact that the "hieratic" acting was only half-heartedly done - as is often the case when a director decides to do it - was that the outer acts were stripped of any dramatic impact and reduced to a mere visual feast. The crux of the drama - deep-freezing the baby - may be in act two, but Jenufa is disfigured for life in act one and the baby does, after all, thaw out in the middle of her wedding in act three...

And though Jeanne-Michèle Charbonnet is a great actress, the grim and grimy reality of act two was not especially convincingly directed, and stuffing the baby's clothes into the freezing compartment in an act of madness before collapsing at the end was simply odd.

Vocally, Andrea Danková was an excellent Jenufa. Jeanne-Michèle Charbonnet has no top left and has to resort to screams instead of singing, but as I just said she's still a great actress with striking presence and this "cheating" is therefore done to great effect. They made a very fine pair. Nicky Spence has, I was told, a "big sound" but it didn't make it too well up to where I was sitting. Many people were impressed by Charles Workman's Steva; I bow to them. I'm not keen, as I've often remarked, on his "stiff" sound that, to me, never seems to open up. He's a good actor, but in this production had little chance to show it, being bound up in the stylization.

I read in the press that Ludovic Morlot was at least better in Janacek than in Mozart. To me, this Jenufa sounded more like a reading than a performance, lacking in variety and subtlety.

Jenufa should be electrifying. This lavish but conspicuously self-conscious production has been described as "magical". To me it was just a disappointment.

.jpg)