La Monnaie, Brussels, Sunday October 26 2014

Conductor: Koen Kessels. Choreography and production: Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. Sets and videos: Eugenio Szwarcer. Costumes: Khanh Le Thanh. Lighting: Willy Cessa. Soprano: Claron McFadden. Mezzo-soprano: Sara Fulgoni. Counter-tenor: Gerald Thompson. Tenor: Ed Lyon. Bass: Mark S. Doss. Dance: Eastman - Aimilios Arapoglou, Damien Jalet, Jason Kittelberger, Kazutomi Kozuki, Elias Lazaridis, Johnny Lloyd, Nemo Oeghoede, Shintaro Oue, Guro Nagelhus Schia, Ira Mandela Siobhan. Child sopranos: Gabriel Kuti, Theo Lally, Gabriel Crozier. Orchestra and Chorus of La Monnaie.

“Whether you call it shell shock or post-traumatic stress disorder, war creates serious psychological wounds. A hundred years after the outbreak of the Great War, Belgian composer Nicholas Lens and Australian author and musician Nick Cave have written a new opera on this theme. In twelve poems or canti he evokes the anonymous protagonists of the war in a highly personal and fluent style: soldiers, mothers, orphans, prisoners, etc. The testimonies of these individual characters, with whom everyone can identify, make the universal call for a humane and peaceful world. […] This new creation by La Monnaie has been incorporated into the official calendar of the Federal Committee for the Organisation of the Commemoration of World War I.” From La Monnaie’s website.

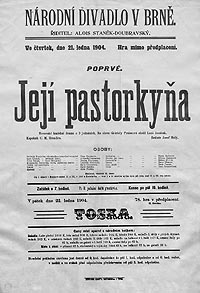

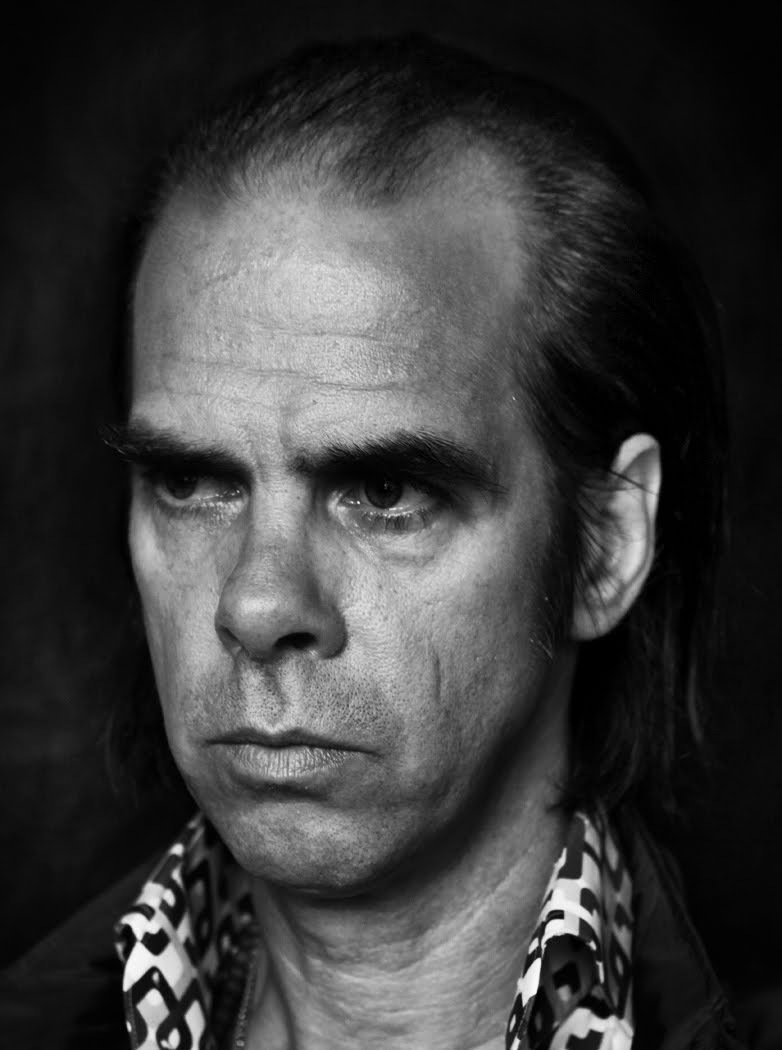

Nicholas Lens calls his new work an opera, and he knows best, but it is subtitled “A Requiem of War” and, as mentioned in the text published by La Monnaie, above, is structured in twelve “cantos” written by Nick Cave. In my usual ignorance, I had to Google to find out who Nick Cave was. If I found his texts flat and uninspiring - “I float, I emote,” for example - that’s probably also more evidence of my ignorance. People used to his songs would know better, and undeniably the overall structure was clear.

I should imagine the kind of shortcut-by-analogy I’m about to take to describe the music drives composers mad, but I see no other simple way to give an idea of what a new work sounds like. It’s somewhere between mature-to-late Britten and Tippett’s A Child of Our Time (without the spirituals), with occasional excursions into Ligeti (the opening especially, reminiscent, no doubt superficially, of the "Dies Irae" of his Requiem) and brief hints of Gershwin. It is accessible to any regular classical-music listener and is often tonal in sound, at times even “traditionally” melodic, but without dumbing-down into easy listening. It calls for a large orchestra, with a piano, a cartload of percussion instruments, and a couple of balloons to burst; so large that at times (but not often) the singers are nearly drowned, making the supertitles especially useful.

The vocal parts are mostly quite conventional; the soprano’s is perhaps the exception, requiring some stratospheric notes closer to screaming than singing. That would explain why Claron McFadden was more stretched than the others in the excellent cast: any soprano (with the possible exception of Yma Sumac, who might, however, have looked out of place in a commemoration of WWI) would be. Sara Fulgoni was so excellent I now wonder why I didn’t admire her Maddalena in Rigoletto. Ignorance again, probably. Perhaps I don’t like the part. Ed Lyon, who comes in for a fair (or rather, unfair) amount of ill-natured stick on websites, seems to me to be firming up and maturing into an excellent English-type tenor. Mark S. Doss was very impressive indeed. Gerald Thompson started out less so, but improved as the work progressed.

Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s staging was legible and neatly executed, seamlessly combining acting, dance, video and scene changes. The stage was white, with a white rear wall that folded into terraces of various heights, making platforms for the performers, or video screens. (At the beginning the dancers, dead, dropped off these high shelves alarmingly.) The men's costumes were the various uniforms of the armies at war, and to create a sense of sheer number, of wave after wave of soldiers and officers thrust to their deaths, the performers appeared in different uniforms as the afternoon went on. The soprano, a universal wife-and-mother figure, wore a plain, wifely, motherly, maroon dress.

The dancers, nearly all men, kept up a kind of perpetuum mobile, not only dancing (writhing expressively) and dying in quick succession, over and over, rolling from stretcher to stretcher, but shifting around, as they danced, a small selection of props: sandbags, wooden crosses, stretchers and rifles, and using them to create new spaces or structures on stage. The singers, both soloists and chorus, were incorporated, as I just said, seamlessly into this carefully-choreographed action. Videos of soldiers in various positions: crouching, crawling, shooting, falling, dead… were projected on to the floor – this was very effective from where I sat but presumably less so from the stalls – and equally effectively on to plain white cut-out figures lined up on the terraces.

The production was, overall, impressively slick – which was the one thing about this excellent show that “bugged” me a tiny bit: the war itself was, of course, a humongous, lethal mess.

This is a work it would be good to listen to at home, or better still watch. I see La Monnaie willl stream it in November. Perhaps, after that, it will be available to buy. I’d like to.

Conductor: Koen Kessels. Choreography and production: Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. Sets and videos: Eugenio Szwarcer. Costumes: Khanh Le Thanh. Lighting: Willy Cessa. Soprano: Claron McFadden. Mezzo-soprano: Sara Fulgoni. Counter-tenor: Gerald Thompson. Tenor: Ed Lyon. Bass: Mark S. Doss. Dance: Eastman - Aimilios Arapoglou, Damien Jalet, Jason Kittelberger, Kazutomi Kozuki, Elias Lazaridis, Johnny Lloyd, Nemo Oeghoede, Shintaro Oue, Guro Nagelhus Schia, Ira Mandela Siobhan. Child sopranos: Gabriel Kuti, Theo Lally, Gabriel Crozier. Orchestra and Chorus of La Monnaie.

“Whether you call it shell shock or post-traumatic stress disorder, war creates serious psychological wounds. A hundred years after the outbreak of the Great War, Belgian composer Nicholas Lens and Australian author and musician Nick Cave have written a new opera on this theme. In twelve poems or canti he evokes the anonymous protagonists of the war in a highly personal and fluent style: soldiers, mothers, orphans, prisoners, etc. The testimonies of these individual characters, with whom everyone can identify, make the universal call for a humane and peaceful world. […] This new creation by La Monnaie has been incorporated into the official calendar of the Federal Committee for the Organisation of the Commemoration of World War I.” From La Monnaie’s website.

|

| Nicholas Lens |

I should imagine the kind of shortcut-by-analogy I’m about to take to describe the music drives composers mad, but I see no other simple way to give an idea of what a new work sounds like. It’s somewhere between mature-to-late Britten and Tippett’s A Child of Our Time (without the spirituals), with occasional excursions into Ligeti (the opening especially, reminiscent, no doubt superficially, of the "Dies Irae" of his Requiem) and brief hints of Gershwin. It is accessible to any regular classical-music listener and is often tonal in sound, at times even “traditionally” melodic, but without dumbing-down into easy listening. It calls for a large orchestra, with a piano, a cartload of percussion instruments, and a couple of balloons to burst; so large that at times (but not often) the singers are nearly drowned, making the supertitles especially useful.

|

| Nick Cave |

Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s staging was legible and neatly executed, seamlessly combining acting, dance, video and scene changes. The stage was white, with a white rear wall that folded into terraces of various heights, making platforms for the performers, or video screens. (At the beginning the dancers, dead, dropped off these high shelves alarmingly.) The men's costumes were the various uniforms of the armies at war, and to create a sense of sheer number, of wave after wave of soldiers and officers thrust to their deaths, the performers appeared in different uniforms as the afternoon went on. The soprano, a universal wife-and-mother figure, wore a plain, wifely, motherly, maroon dress.

|

| Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui |

The production was, overall, impressively slick – which was the one thing about this excellent show that “bugged” me a tiny bit: the war itself was, of course, a humongous, lethal mess.

This is a work it would be good to listen to at home, or better still watch. I see La Monnaie willl stream it in November. Perhaps, after that, it will be available to buy. I’d like to.